About the author | About the book | Author's notes

"I was raised listening to my mother's âcimisowina [autobiographical vignettes], I was not surprised that many of the Indigenous authors in Canada I had begun reading as an adult included - and relied upon - their own life stories. What did surprise me, however, was that this archive has been understudied and undervalued."

About the author

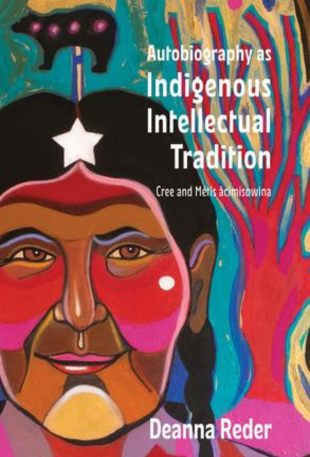

Deanna Reder (Cree-Métis) is Full Professor in the Department of Indigenous Studies and the Department of English at Simon Fraser University. She is one of the founding members of the Indigenous Literary Studies Association (ILSA) and served as the Series Editor for the Indigenous Studies Series at Wilfrid Laurier University Press from 2010 to 2021; she is a founding member of the Indigenous Editing Association (IEA), established in 2019, and has been a co-Chair of the Indigenous Voices Awards since its inception in 2017 (see Indigenousvoicesawards.org). Professor Reder is the research lead for "The People and the Text: Indigenous Writing in Northern North America in Lands Claimed by Canada" (see www.thepeopleandthetext.ca). She is the co-editor of four anthologies, two of which are foundational to the field of Indigenous Literary Studies in Canada (Learn, Teach, Challenge: Approaching Indigenous Literatures, 2016; Read, Listen, Tell: Indigenous Stories from Turtle Island, 2017). She co-edited, with Sophie McCall, the fiftieth anniversary issue of Ariel: a Review of International English Studies in 2020 and co-edited a 2022 issue on pedagory in Studies in American Indian Literatures with Dr. Michelle Coupal. In 2022 her monograph, Autobiography as Indigenous Intellectual Tradition was released, winning the 2023 Gabrielle Roy Prize from the Association of Canadian and Quebec Literatures and in 2024 her book has received the Modern Languages Association for Native American Literatures, Cultures and Languages. Reder was inducted into the College of New Scholars in the Royal Society of Canada in 2018.

About the book

Autobiography as Indigenous Intellectual Tradition critiques ways of approaching Indigenous texts that are informed by the Western academic tradition and offers instead a new way of theorizing Indigenous literature based on the Indigenous practice of life writing.

Since the 1970s non-Indigenous scholars have perpetrated the notion that Indigenous people were disinclined to talk about their lives and underscored the assumption that autobiography is a European invention. Deanna Reder challenges such long held assumptions by calling attention to longstanding autobiographical practices that are engrained in Cree and Métis, or nêhiyawak, culture and examining a series of examples of Indigenous life writing. Blended with family stories and drawing on original historical research, Reder examines censored and suppressed writing by nêhiyawak intellectuals such as Maria Campbell, Edward Ahenakew, and James Brady. Grounded in nêhiyawak ontologies and epistemologies that consider life stories to be an intergenerational conduit to pass on knowledge about a shared world, this study encourages a widespread re-evaluation of past and present engagement with Indigenous storytelling forms across scholarly disciplines.

Partly because I was raised listening to my mother’s âcimisowina [autobiographical vignettes], I was not surprised that many of the Indigenous authors in Canada I had begun reading as an adult included—and relied upon—their own life stories. Whatever the genre—be it history, political commentary, public address, literary criticism, or journalism—I noted that writing by Indigenous authors integrated autobiographical detail. I always recognized both the self-worth and high regard for the opinions of others implicit in this practice. What did surprise me, however, was that this archive has been understudied and undervalued.

This binary that conceives of Indigenous discourse as primarily oral and European discourse as primarily literary is a false divide that ignores the complex reliance of all cultures on a spectrum of literacies. It also gives the European chauvinist the justification to ignore Indigenous literary production, reifying the false binary between the spoken and the written. Moreover, it distracts us from acknowledging the dismal access that Indigenous authors historically have had to publication. While this book primarily recognizes the impact of nêhiyawi-itâpisinowin [Cree worldview] on Cree and Métis literatures, it is impossible to discuss Indigenous literatures in Canada without also noting the crippling effects that the publishing and editing industry have had on all Indigenous literary production.

All through public school and up until my PhD, I never was taught by an Indigenous professor and I rarely was assigned literatures by Cree and Métis authors. My hope is that this award will validate the aim of my monograph, which is inspire more archival work on Indigenous texts and also encourage emerging Indigenous scholars to consider their cultural understandings as valuable contributions to their scholarship.

My research on the neglected Indigenous literary archive continues, as part of my research, as does my work with SFU colleague Dr. Sophie McCall and UBC professor Dr. Billy-Ray Belcourt, to co-Chair the Indigenous Voices Awards, as a way to value the writers of the past and encourage the writers of the future.