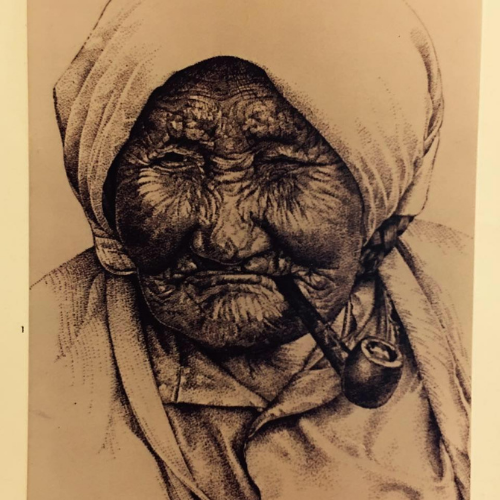

Reconciliation reminds me of my dìdųų (great grandmother), Julienne The’dahcha (one who carries a feather). This Gwichyà Gwich’in matriarch was born in 1889 and had many accomplishments: she was a trapper, moose hide tanner, mother, linguist, cultural negotiator, and witness to the signing of Treaty 11. In our family, she is famous for driving her dog team across the North, between what is now Alaska, the Yukon, and the Northwest Territories. Julienne also experienced the institutionalization of her children in Indian Residential Schools, the opening of the first liquor stores in the Northwest Territories, and the increasing fragility of our language, Dinjii Zhuh Ginjìk – the only language she had known as a child. In her lifetime, dìdųų reconciled far more than anyone has from my generation.

As a response to Canada 150 in 2017, Sara Komarnisky and I co-authored “150 Acts of Reconciliation for the Last 150 Days of Canada’s 150.” My frustration around the dismal efforts of Canadian politicians, bureaucrats, churches, and corporations to take up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 94 Calls to Action had combined with my anger toward the federal government’s announcement that it would spend $500 million on Canada’s 150th birthday in Ottawa. Half a billion dollars can buy a lot of clean drinking water. Or bring Indigenous education on reserves up-to-par with non-Indigenous schools in this country. Half a billion dollars seemed ridiculous, unnecessary, and, in fact, insulting.

I recalled dìdųų’s teachings: that Dinjii Zhuh – Indigenous Peoples – have both the responsibility and the burden of making things better, not necessarily for ourselves but for generations to come. Back in 1983, when we lost Julienne, no one talked about reconciliation, Indian Residential Schools, or colonial trauma. Yet each of these concepts was present and visible, shrouded under different names such as “Indigenous language renewal,” “Land Claim Agreements,” and “Native activism.” But in fact, this was reconciliation. And dìdųų was my first and best teacher about what reconciliation means and how it can be practiced.

Because reconciliation is just that: a practice.

Reconciliation is a commitment to practice sitting with discomfort at your workplace or home, at the gym, or with your co-workers or family members. Like any practice, this will take time, self-reflexivity, and hard work. As you work through “150 Acts,” you might question deep-seated core beliefs. You might laugh, or cry, or become angry. This is part of the process. And you should be assured that as the authors – a Gwichyà Gwich’in historian and a Ukrainian-Canadian settler anthropologist – we stand alongside you. We, too, sit with our discomfort and reflect on how we can do better, what reconciliation means, and how to best chip away at the colonial fabric of our academic institutions.

2017 – the year “150 Acts” was born – was a different time than 2021. Colton Boushie was a vivacious young Cree teenager, not a victim of a gunshot to the head. The Trudeau government had not yet purchased a pipeline, and had won its first election on (arguably) its platform on reconciliation. Institutions had not yet dismissed the gravity of the Report on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. As such, as a co-author of “150 Acts” in 2017, I failed to point out three crucial points: the ongoing power of white supremacy in Canada, the obvious failures of our governments to advance the 94 Calls to Action, and the tendency of most of us to subscribe blindly to ideals that uphold colonialism in our country. I was not yet brave enough. Now I am. Will you join me?

Photograph of Julienne The’dahcha

Équité, diversité et inclusion dans le système de recherche postsecondaire

← Page d'accueil du balado Voir Grand Description | À propos de l'invitée | À propos du rapport | Transcription | Suivez nous Description En début d'année, le Conseil des académies canadiennes a publié son rapport intitulé « Équité, diversité et...

Vivre-ensemble

Par Prof. Margrit Talpalaru, professeur.e et responsable académique pour le Congrès 2025 au Collège George Brown Le Collège George Brown (CGB) est le premier établissement d'enseignement supérieur à accueillir le Congrès des sciences humaines au...

Les prestigieux Prix du Canada de la Fédération sont de retour pour célébrer les meilleurs livres savants

Nous sommes ravi.e.s d'annoncer que les Prix du Canada, la subvention nationale du livre savant de la Fédération, reviennent ce mois-ci sous un nouveau jour afin de célébrer cinq livres gagnants et leurs auteur.trice.s. Désormais, les Prix du Canada...